By Michael Arrieta-Walden

I retired this summer — again.

I was fortunate to have two careers. As I retire for a second time, I am reflecting on both of my careers, and my overwhelming feeling is that I am grateful. I consider myself the luckiest person in the world to have lived two dreams.

I worked as a journalist for almost 30 years and then as a teacher for 15 years. To anyone who is considering changing careers, I urge you to go for it. We only have one life.

I actually flirted with multiple careers, the result of either my chronic attention deficit disorder or simply a lot of interests. During my adult years I also seriously considered becoming a public aid attorney, a history professor and a doctor.

But I landed on journalism and education. I think I loved them both because they both offered a way to help people and an opportunity to learn every day.

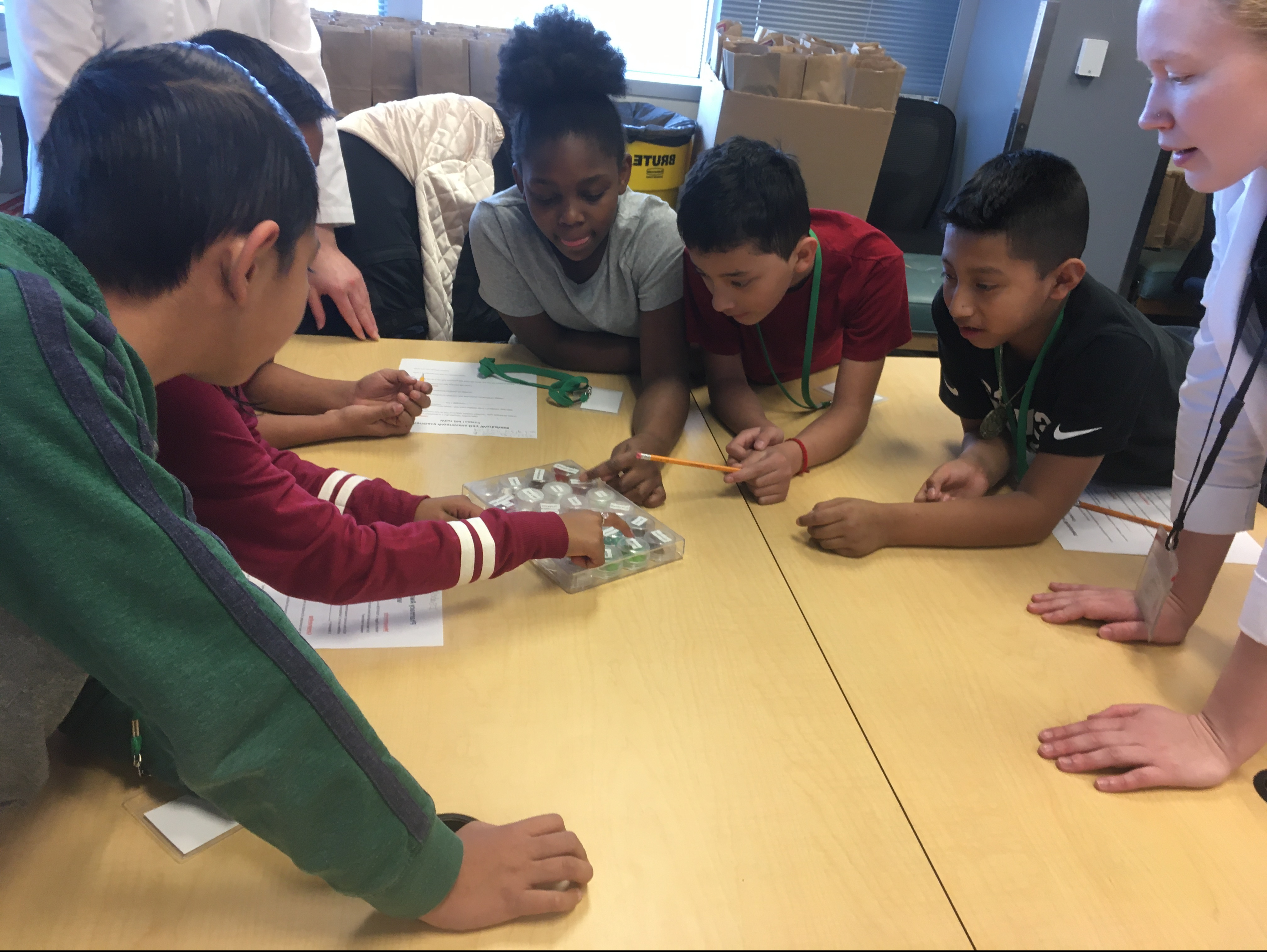

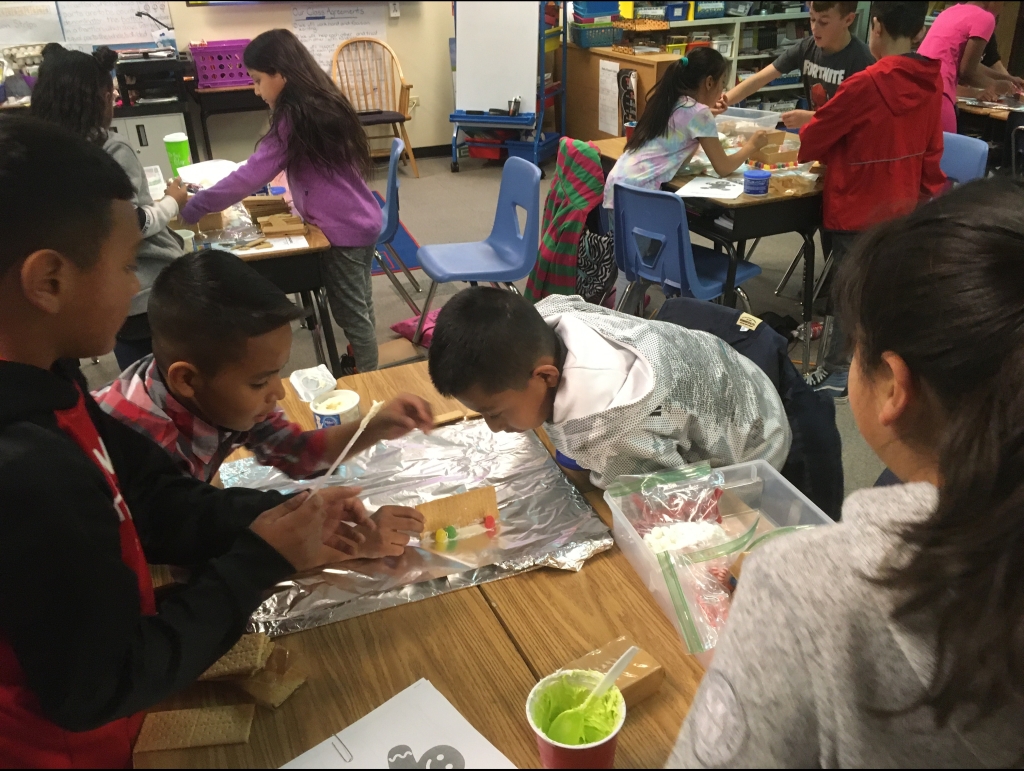

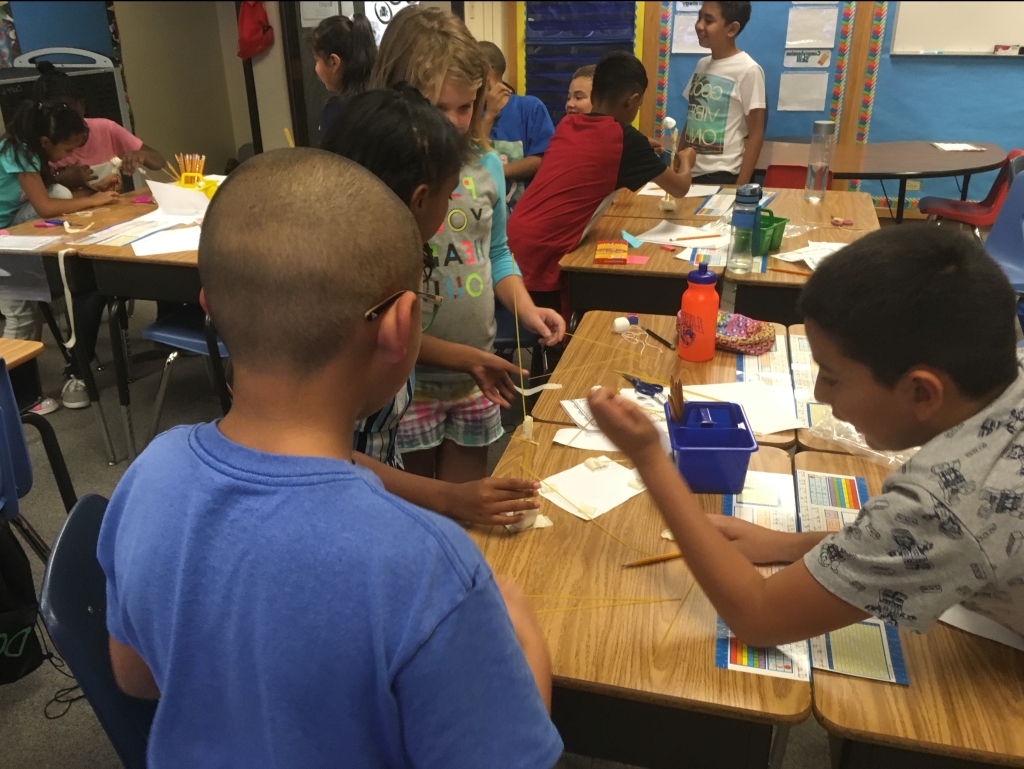

As a journalist, you never knew what each day would bring. With each new story you had to become an instant expert on topics ranging from wildfires to government bonds to local crime. As an elementary school teacher, you not only had to learn how to teach a variety of subjects, you had to respond to the constantly changing needs of your students. And I found I was always learning from them as well.

When I was a journalist, I had so much fun that I often thought, “I can’t believe I get paid to do this!”

As a cub reporter, I had the opportunity to pair up with another reporter, Phil Manzano, to investigate abuses of undocumented workers in Oregon’s forestry industry. The reporting was challenging and exciting. We toured remote camps for tree planters and migrant camps for families. We visited workers in shoddy, rundown housing. We were chased down Mount Hood by angry contractors. Most importantly, our work made a difference. Our series led to congressional hearings and new contracting rules to protect workers. Early in my career, I had a vivid experience of how journalism could make a difference.

Left: When The Albuquerque Tribune won a Pulitzer Prize in 1994, the newsroom of the small newspaper erupted with joy. Right: Sharing laughter at a team stand-up was a daily ritual at The Oregonian.

***

But I decided to become a teacher because I wanted to have a direct impact on people’s lives. I was not disappointed.

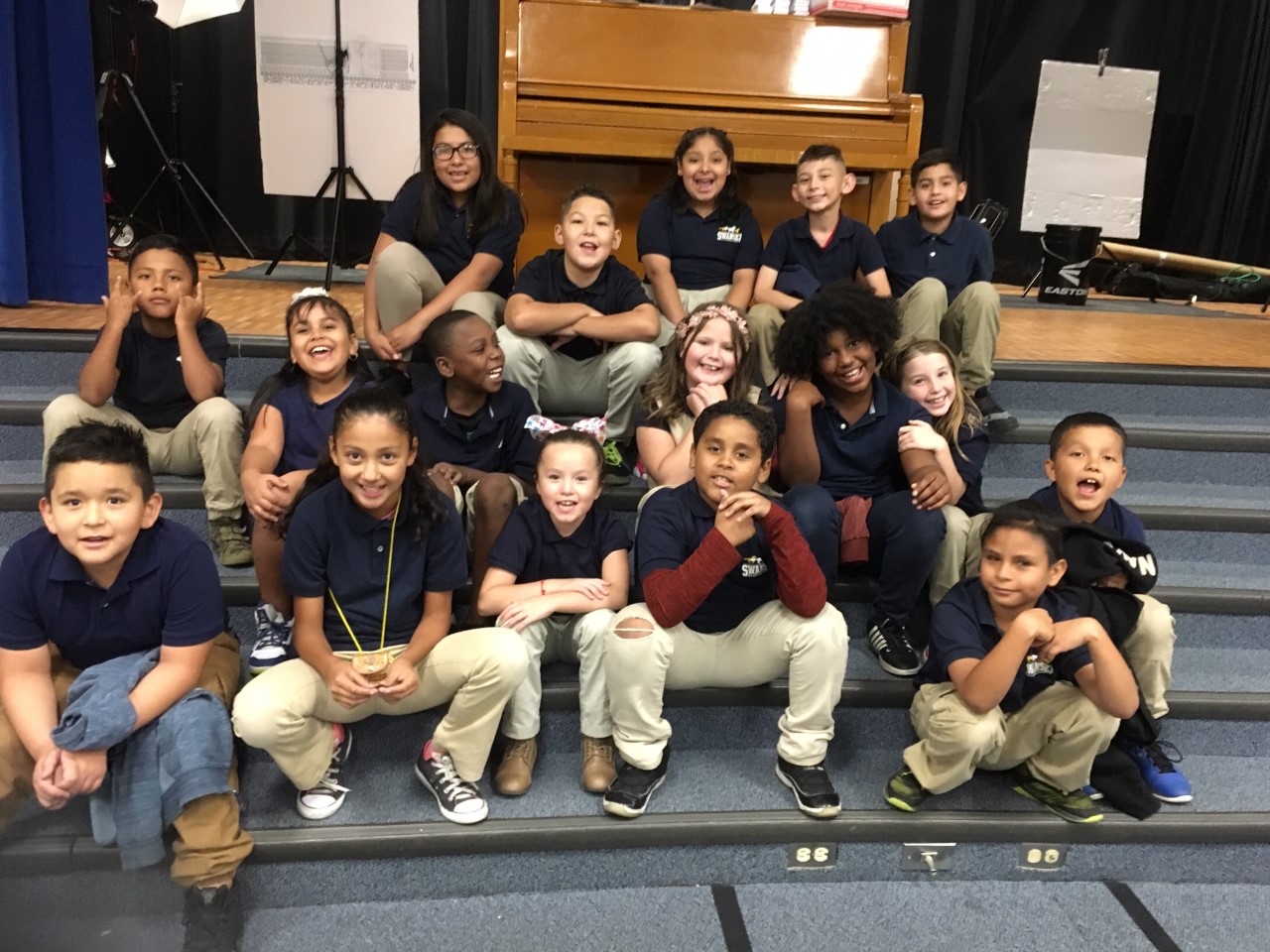

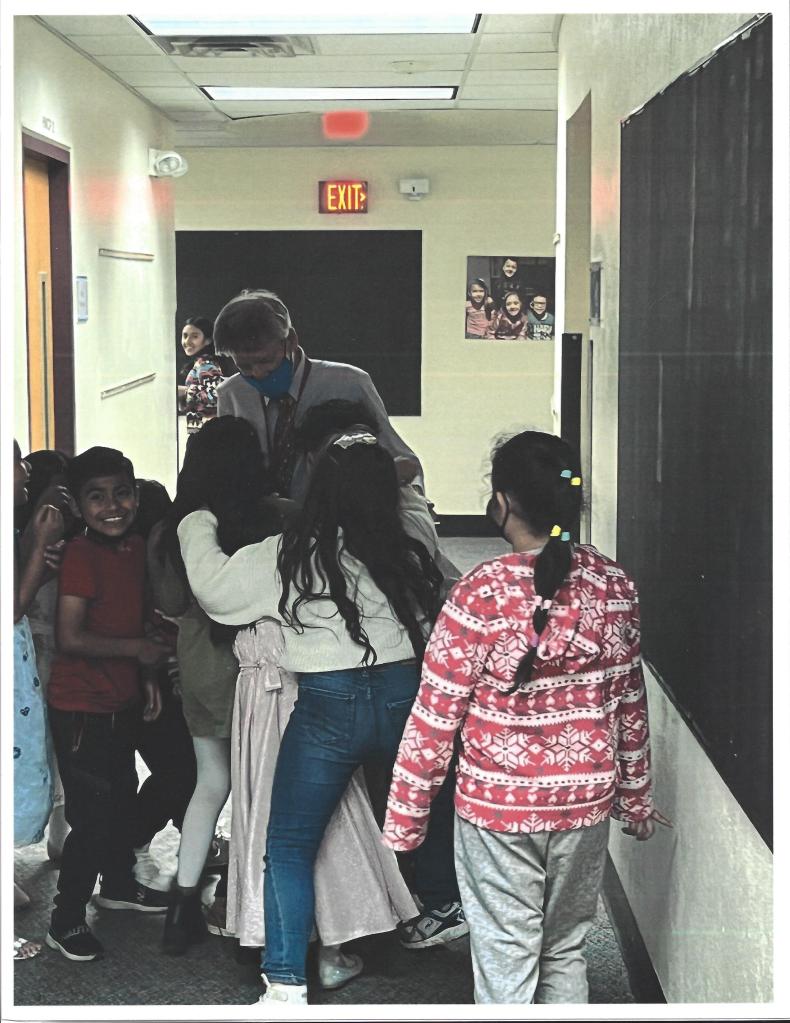

As an elementary school teacher, you receive so much love from your students. The smallest act makes such a difference.

One of my favorite moments was when I helped organize a trip to the beach in Oregon for our fifth-graders. I witnessed unbridled joy when the students hiked through the trees to Oswald West State Park, and the ocean opened up before them. For many, it was the first time they had seen the ocean. As one student wrote at the end of the year, their favorite experience was “going to the beach. It was the first time that I went to the beach and it was so much fun.”

But the two professions are radically different.

A newsroom is like no other place. It’s full of people who are intelligent, curious and aggressive. It is a constant buzz of activity, and it can turn electric in a moment. Journalists can often be cynical and hardened; they must have thick skins to ask tough questions and face relentless criticism.

In contrast, a school is often full of the nicest people you could work with. Unlike journalists, they often lack the confidence to assert themselves. But they are resilient, and no matter how rough the day before has been and despite how little they are paid, most start each day with optimism.

Throughout my teaching career, I often have been asked if I missed journalism.

I did, every day. I have especially missed it as journalists have come under attack and newspapers have declined. Widespread conspiracy theories and false narratives, such as the bogus claims about the 2020 election results, make journalism’s pursuit of truth all the more important.

Yet my life was so enriched by teaching.

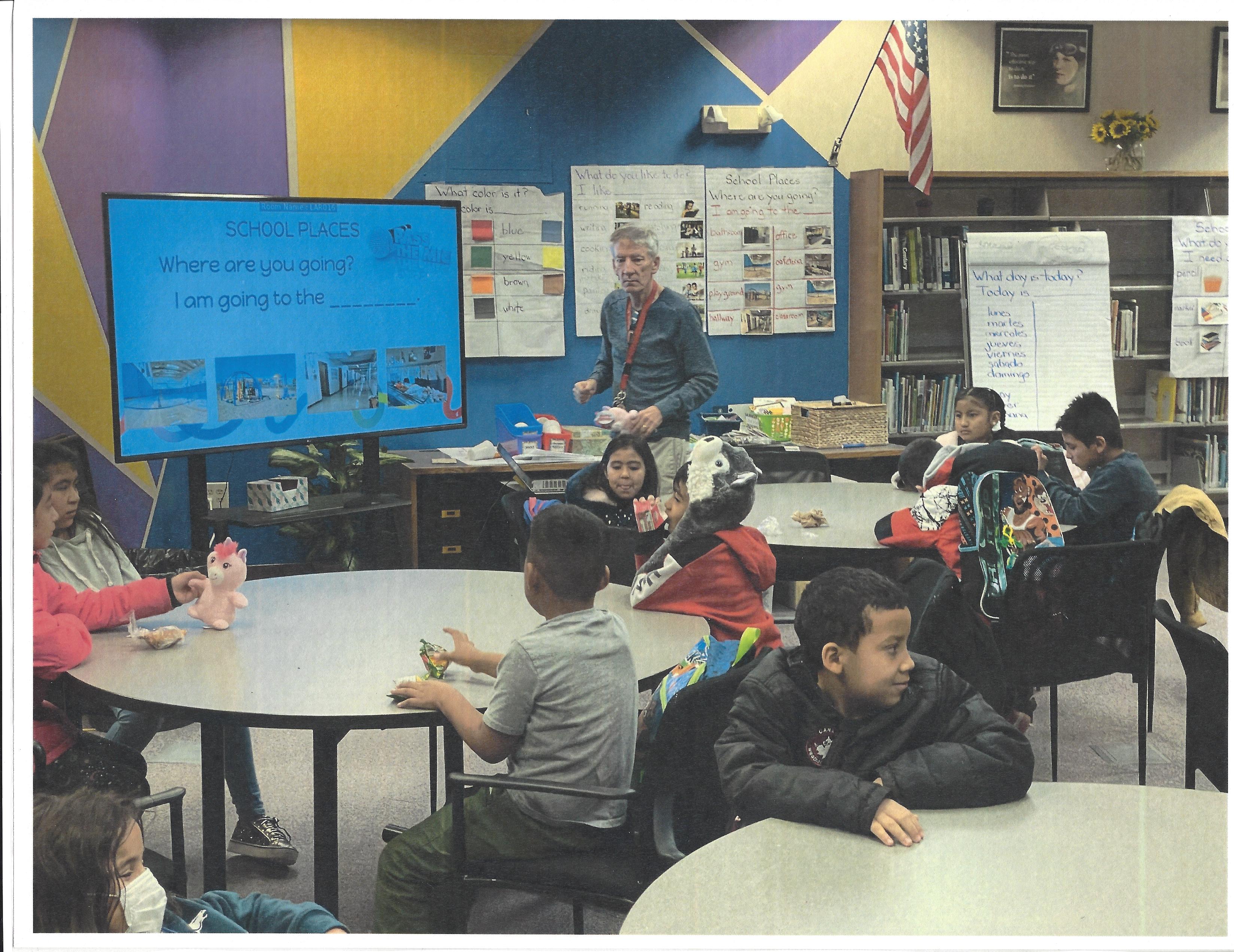

If I had never left journalism I never would have met Jose, whose parents came to Oregon from Mexico seeking a better life for him and his sister. He worked hard to honor their bravery. I would never have seen the perseverance of two sisters whose parents cleaned buildings at night, so they did homework and slept in the family car at night. I would never have been told by a graduating senior that the help I secured for her in fourth grade enabled her to graduate. I would not have had the chance to teach dozens of students their first words in English, or to teach English to their grateful immigrant parents.

What a privilege!

So always follow your heart. You just might find more treasures, like I did.

***

Michael Arrieta-Walden lives in Denver, Colorado with his wife, Fran, who was willing to sustain a huge drop in income when he chose teaching. Mike retired as an elementary school teacher in Aurora Public Schools in July and left The Oregonian in Portland, Oregon in 2008 as a managing editor.

Editor’s note: I was fortunate to work with Mike in two newsrooms — in Salem, where he made a fabulous first impression as a college intern, and in Portland, where he and his wife landed after I helped recruit them to The Oregonian. Mike is too modest to mention that he was the editor on the Pulitzer-winning stories in Albuquerque that related the experiences of Americans who had been used unknowingly in government radiation experiments nearly 50 years ago. When he left The Oregonian to pursue teaching, we knew he’d make just as big an impact in the classroom as in the newsroom. You can see that he did.

Tomorrow: Lynn St. Georges, “Return to sender”